Travel, for us, is almost always a joyous occasion. New cultures, new flavors – a window into the beauty of our world. However, not everything in the world is beautiful, and we feel it would be irresponsible and even dangerous to pretend otherwise. This is why, in the middle of our exuberant visit to Munich to celebrate Oktoberfest, we found ourselves making a short journey that somehow felt interminably long.

It is difficult to live and travel in Europe without some sense of a dark cloud hanging over all this at times. World War II was not that many years ago, and the Europe we see now is a direct result of it. Signs of that terrible period remain, even in the most beautiful places; for example, history certainly tainted that gorgeous library in Vienna with the balcony from which Hitler spoke.

Sometimes a historically significant place lies just outside a major touristic destination. When we went to Bilbao, for example, we made sure to make time to see Guerinca, the site of a bloody aerial bombing during the Spanish Civil War. So when we saw that Dachau, the site of Nazi Germany’s first concentration camp in Germany, is a mere 10 miles from Munich, we knew we had to leave the festivities behind for an afternoon at least. Doer in particular, a Jewish man with grandparents who fled Hitler’s regime, is often beset by Grandma’s comments during our European travels like, “why would you ever want to go back?”

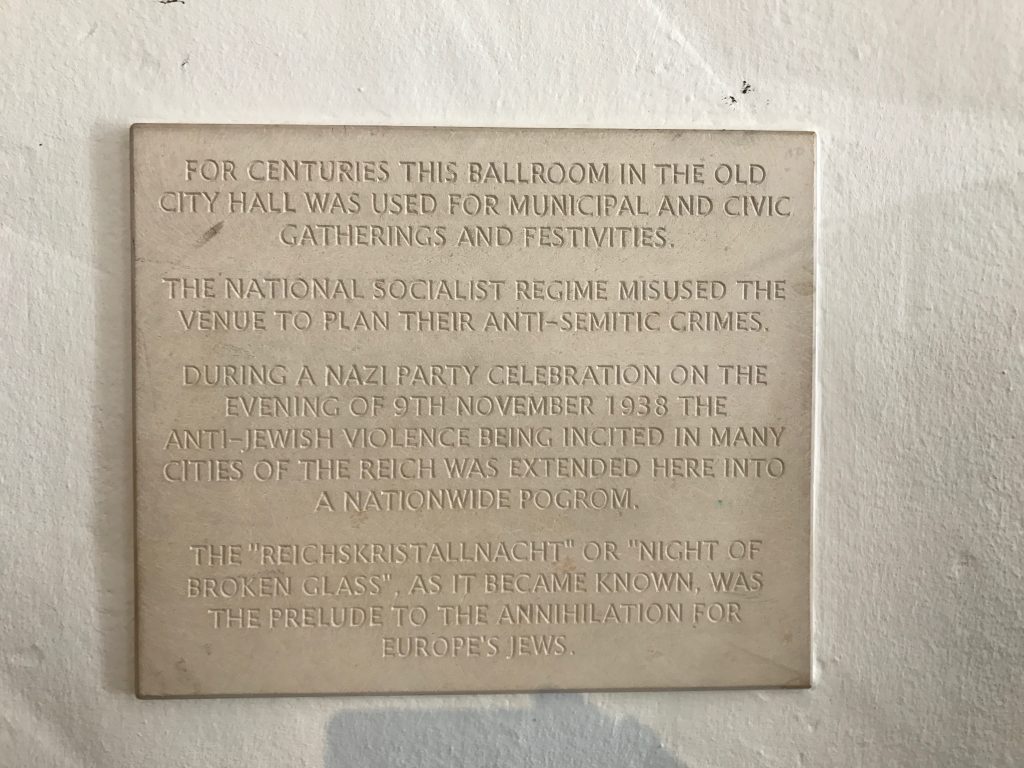

That dark cloud was more apparent than usual while we were visiting Munich, despite the merriment of Oktoberfest. How odd and bizarre, in some ways, for us to be enjoying the culture and dress of Bavaria, which was also the birthplace of the Nazi Party. Indeed, even as we enjoyed a magical performance of a street band one night, we couldn’t help but notice they were performing next to a sign that said, “Kristallnacht started here,” referring to a government-condoned campaign of violence against Jewish people and their homes, businesses, and places of worship.

Greeting visitors to Dachau is the old gate emblazoned with “Arbeit macht frei,” a German phrase meaning, “work sets you free.”

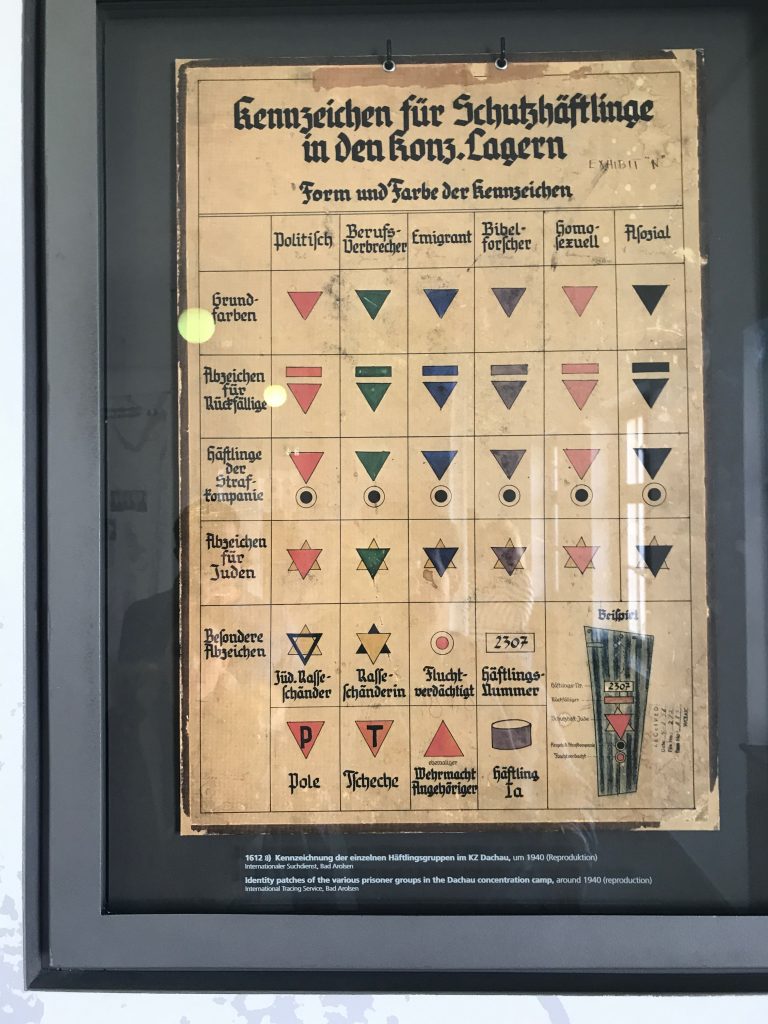

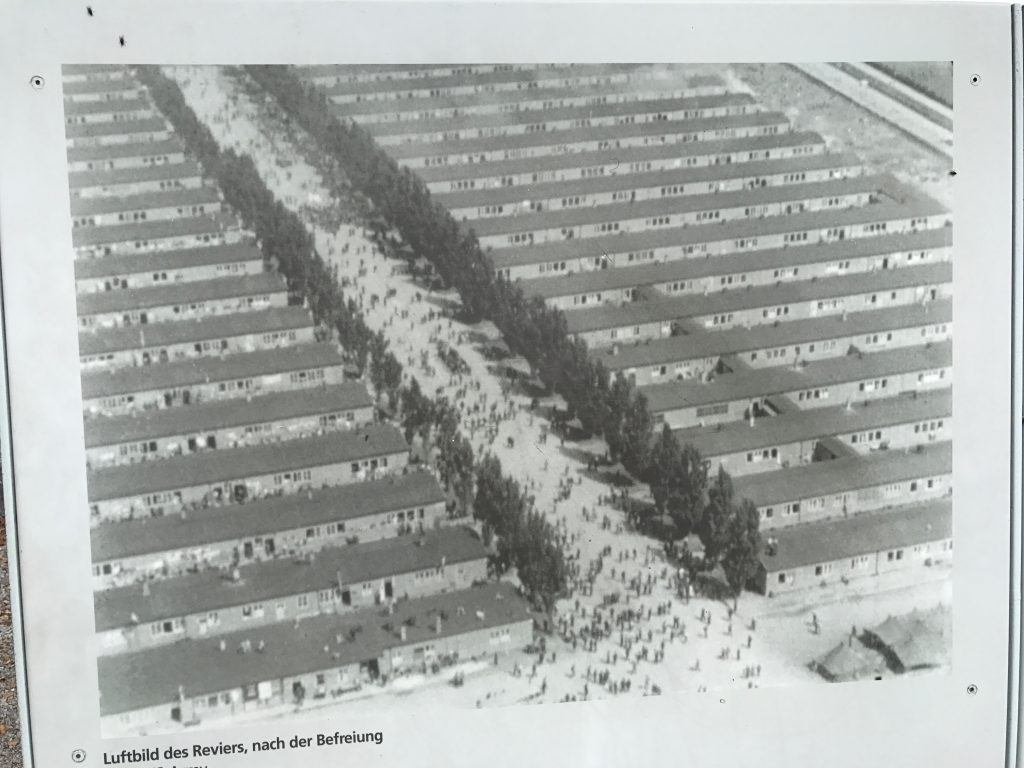

Established in 1933, Dachau became a model for subsequent concentration camps. The group that maintains the camp as a memorial today is tasked with ensuring that this camp and similar sites “testify to the crimes of National Socialism, are places for remembering the suffering of the victims, and act as places of learning for future generations.”

As Dachau is so close to Munich, we knew this was a journey we had to take – to bear witness as they say. But it was certainly a somber day. It is difficult to imagine worse conditions, yet they say Dachau had better conditions compared to some of the other camps. We will certainly visit those other sites in our future travels as well, to understand what our ancestors fought against so that we may be here today.

Behind the barracks lay the memorial sites for several religions.

Near the end of our visit, we arrived at the crematory at the back of the grounds, which was every bit as horrific as one would expect.

Countless bodies were buried in the garden behind the crematory – the Grave of Thousands Unknown.

The horrible things people have done (and continue to do) to one another may never become easier to process or reconcile, but maybe that’s the point: we should never be at peace with such a visit, nor shall we ever forget.

Well written. Words are hard to describe the horrible treatment of so many people during that period.