A flimsy pretense was all we needed to schedule a return trip to Barcelona for the first weekend of April. We’re game pretty much any time, but when Dreamer found out a friend was performing comedy there the coming Saturday evening, the decision was easy.

Our first two trips of Barcelona were quite heavy on the works of Antoni Gaudí, the most famous person associated with Catalan Modernism. While we did devote some time to our favorite whimsical architect (which we’ll tell you all about in our next post), we also discovered another master, Lluís Domènech i Montaner, who designed two modernist gems eventually designated UNESCO World Heritage sites: a music hall and a hospital.

Palace of Catalan Music

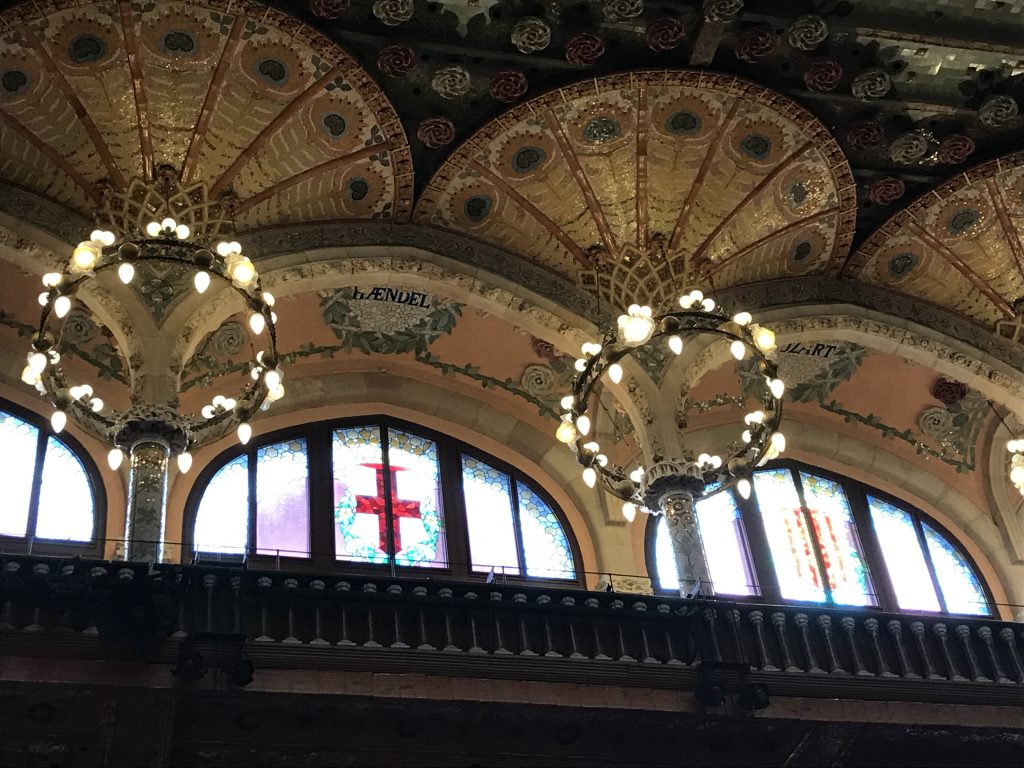

We had already read about the Palau de la Música Catalana, designed by the architect Lluís Domènech i Montaner around the turn of the 20th century, in the American writer James Michener’s account of his adventures in Spain. Apparently, old James was pretty struck by this place, which was built between 1905 and 1908.

We were struck, too. We have to admit, it is a dramatic space in which to stage a performance. Anyone can buy (reasonably-priced) tickets to current shows, too! Props for making this accessible to the general public.

Palau means “palace” in Catalan, and the name certainly fits the opulent building, which was created as a home for the Orfeó Català, a choral society based in Barcelona. The structure really is a monument to Catalan pride.

Moreover, it’s breathtaking. The concert hall is the only one in Europe illuminated entirely by natural light during daytime hours.

Most of the building materials are from the region of Catalonia; the organ, which is from Germany, is the only major non-Catalan piece.

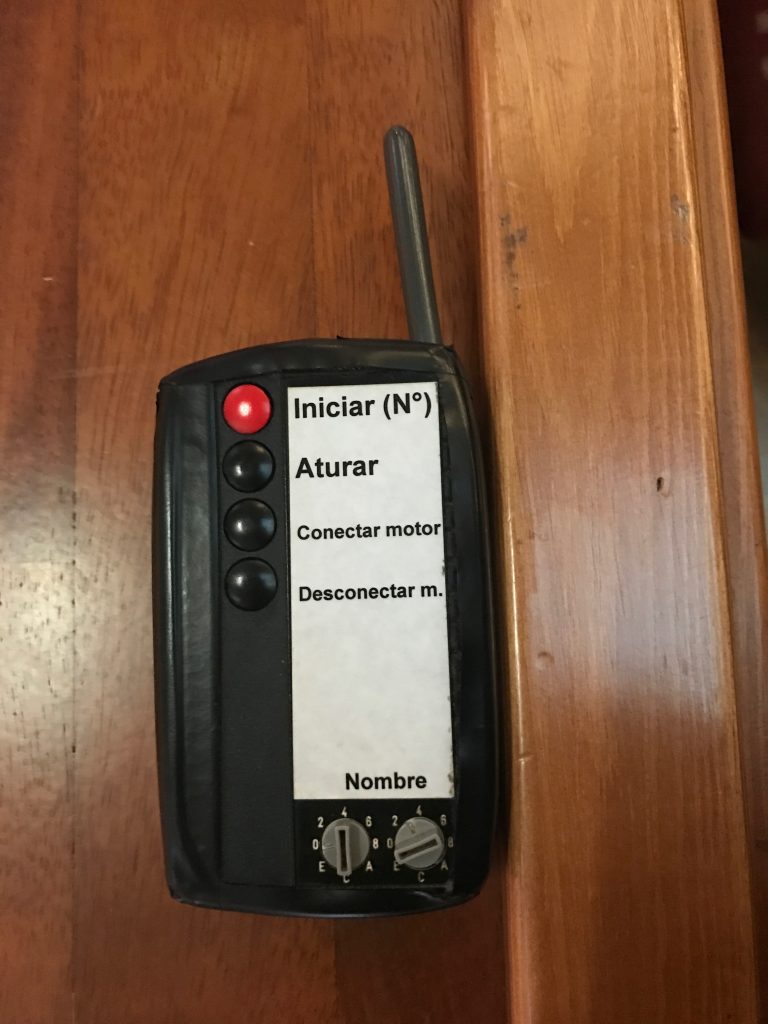

The organ is now computer-controlled, which means it has a remote control all the tour guides can use to play Bach’s Toccata. It sounded real good.

Speaking of remote controls . . .

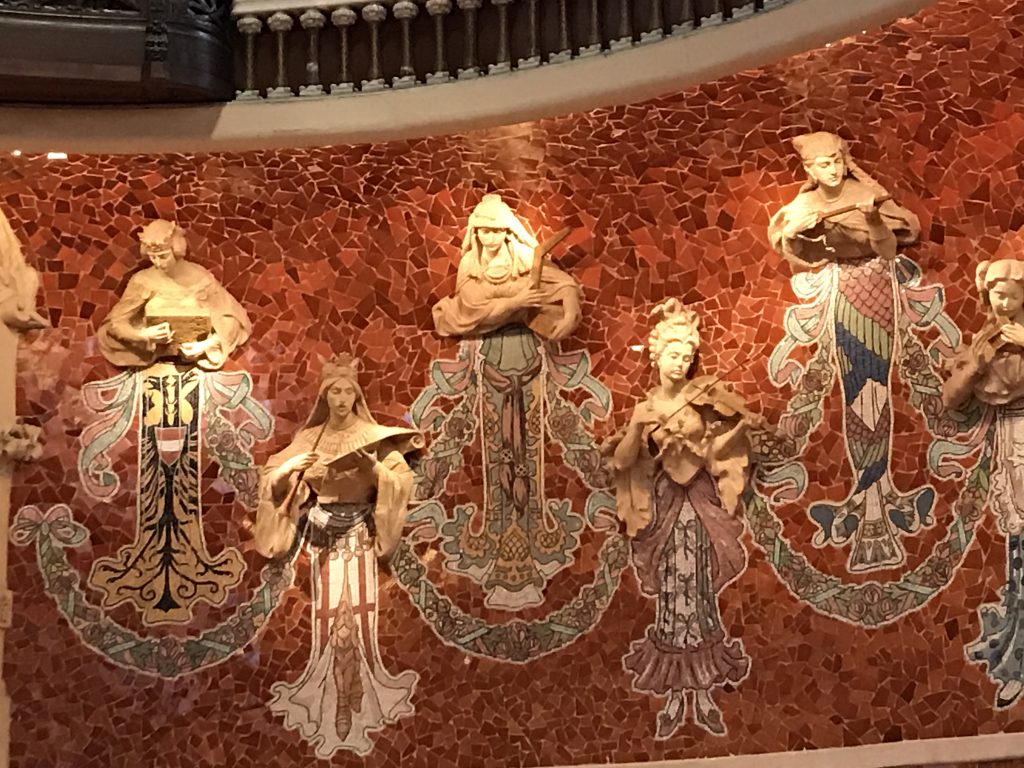

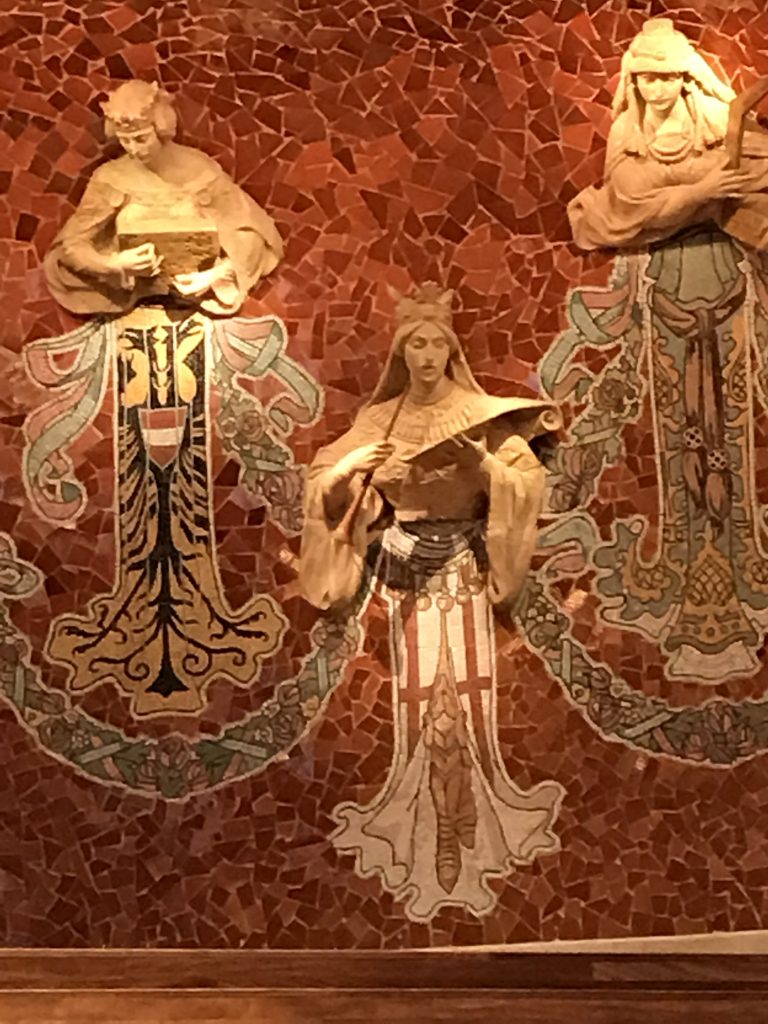

But we digress. In addition to the organ, the stage is famous for its muses, the figures of 18 women inspired by mythology; our tour guide told us they represent the universality of music.

Our guide, Esther, helped us understand the history of the place. And yeah, we really liked her name. Did you know the seats are made out of acoustic material so that the absorption of sound waves is the same whether someone is seated in each chair or not?

Dreamer’s favorite part was the balcony outside the Lluís Millet hall; the columns may be one of the finest examples we’ve seen of trencadís, mosaic made from broken tile shards.

We thought we were impressed with the main level and the patio, but when we ascended into the balcony, we were blown away all over again.

Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau

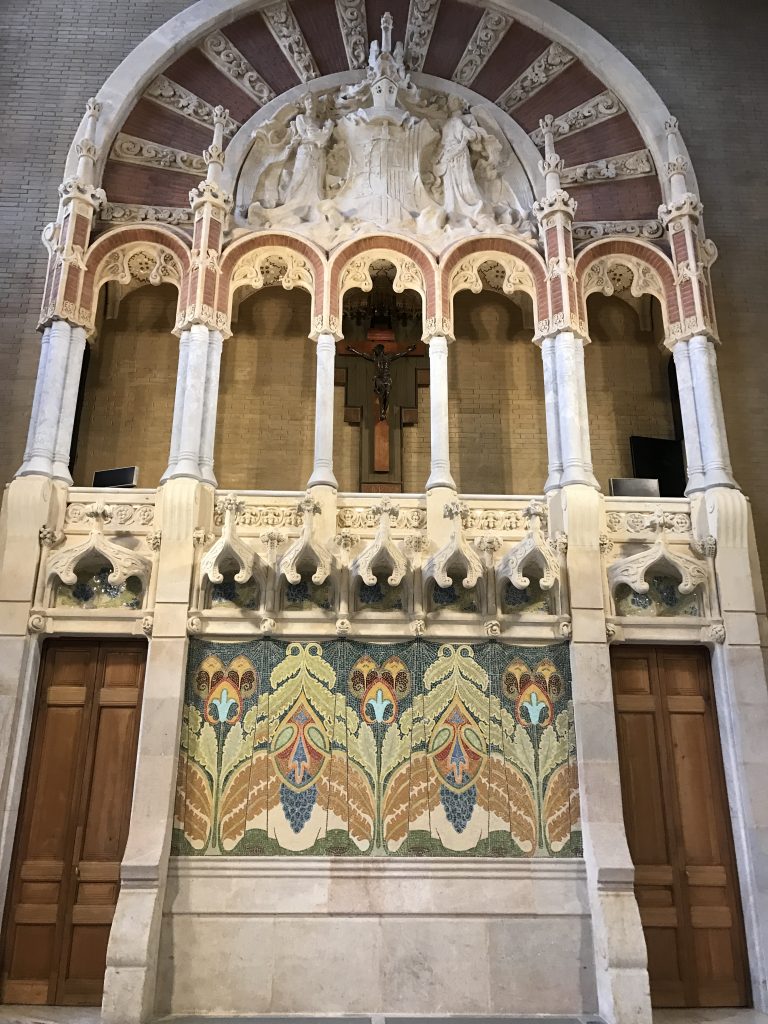

We were fortunate to stay in a hotel just across the street from this next modernist landmark, which was also designed by Montaner (the same architect as the music hall). Remarkably, this complex was still in active use as a hospital until 2009, when it was renovated and turned into a museum. Can you imagine being a patient here? It’s really like no other medical facility we’ve ever seen.

In addition to its beauty, the complex is renowned as the site of two milestones in Spanish medicine: the first bone marrow transplant and the first successful heart transplant.

The original medical facility, Hospital de la Santa Creu, was founded in the Raval neighborhood of Barcelona in 1401. It thrived as a hospital and as a center for teaching and scientific activity for 500 years, but over the centuries, it became outdated – as things tend to do over the centuries. The hospital eventually moved to the new Sant Pau Art Nouveau Site, which was built between 1902 and 1930.

Surrounded by gardens and connected by an underground network of more than one kilometer of tunnels, the site was conceived of as a city within a city. The tunnels facilitated transport of patients and staff, and they routed the hospital’s supply of steam, water, gas, and electricity, as well as the distribution of meals, laundry, and medication.

As if this place needed more modernist street cred: Antoni Gaudí, the artist most associated with Catalan Modernism, died here in 1926, days after he was hit by a tram.

The only downside to this place was the temporary exhibition: a photography showcase put on by a leading camera maker named after a mountain in Greece. What. A. Cluster. We went to see the building the exhibition was in and we were ushered into the exhibition without even realizing what was going on. Once the throngs of people standing around became apparent, we made for what was clearly marked with a European regulation exit sign.

“No,” we were told, “you have to go all the way through the exhibit.” We have never felt so claustrophobic! We breathed a huge sigh of relief when we finally made it out of this oddity. Ironically for a photography exhibit, no photos were taken.